July 1, 2023

We’ve all heard of caregiver burnout. The Cleveland Clinic defines this phenomenon as a “state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion” caused by the demands of caring for another person. With our country experiencing a historic caregiver shortage and nearly 1 in 3 Americans leaving the workforce to provide family care, this is a pressing and long-overdue conversation.

Among paid caregivers, wages are low and most often position these essential workers live at the poverty line. The inability to make ends meet on these meager salaries perpetuates a desperate cycle of unmet needs from all angles.

Yet something crucial is missing from our societal discourse: where is the discussion about care recipient burnout?

As one of millions of Americans in need of ongoing personal care support, I can attest that the strain of needing assistance with nearly every aspect of my existence, from taking a shower to scratching my back, is ever-present, despite my loving and devoted family and my relatively good luck finding reliable paid staff.

I frequently joke that maintaining this body is like the group project that never ends, with some project participants rotating faster than I’d like and the pervasive concern that my MVP groupmates (Mom and Dad) will suffer crumbling backs and necks on my behalf. Worse even is the knowing that I will not be able to wipe their butts in return when the time comes.

And then of course, there is the nearly unspeakable truth that disabled people with high support needs are not given the luxury of a clear future beyond their parents or other aging primary caregivers.

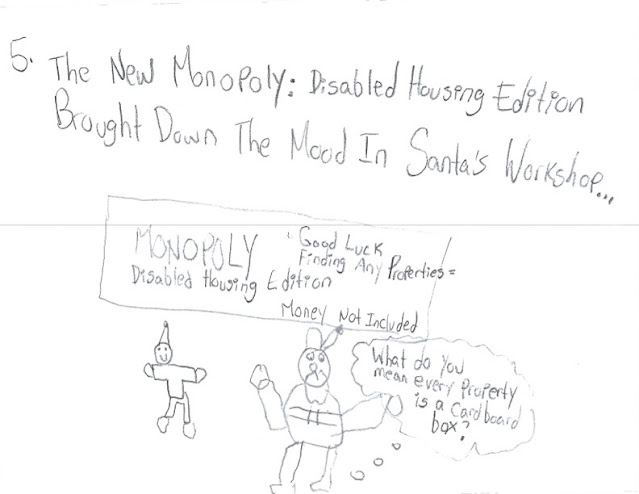

With affordable, accessible housing nearly non-existent, recreational programs for disabled adults sorely limited, and access to covered personal care services intricately intertwined with varying degrees of Medicaid-related poverty, looking too far beyond the next day ahead can feel like a herculean task for many of us.

Writing an ad to find a new personal care assistant feels like a weird cross between a resumé, a dating profile, and a job description, but it’s not some abstract “project in development” or quarterly sales report that rides on a smart hiring decision, it’s your life.

Come across warm and friendly, but not so friendly that your new hire has no boundaries.

Weed out all the applicants who seem afraid of or at least vaguely bothered by your pint-sized dog.

Reiterate that yes, there is lifting involved.

No, this is not private pay.

Yes, experience is great, but not necessary.

OH FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, immediately scrap any applications with the words “angel,” “tender-hearted”, “befriending the handicapped” or “special way with those in need.”

Let down gently those applicants who seem disappointed that you are not an octogenarian paying $60 an hour for a TV watching, grocery fetching “companion.”

And back to the dating profile comparison, silently pray that your most promising applicant doesn’t promptly ghost you upon glancing at the large packet of unfailingly bureaucratic paperwork.

Finding the right person feels a bit like shouting into the void and hoping for a response.

In practice it looks more like selling your “care pitch” on Indeed, on college campus career boards, and in places you once thought were only meant for selling crusty couches in a dark alley, like Craigslist, while hoping you haven’t unwittingly caught the attention of an axe murderer.

Hmmm… you think, maybe a pastel Instagram post created on Canva using a charming photo of you and your dog will draw the ideal clothes changer, butt wiper, and shower giver into your orbit.

If you’re lucky enough to find The One, you dread the moment they inevitably take a higher paying job from the very day they begin working.

This dizzying care-ousel spins onward against the backdrop of a constant battle to convince the State that you are worth caring for in the first place, with a nameless, faceless Medicaid minion eager to reduce the hours of help they begrudgingly award you for purposes of staying alive.

And still, you must carry on juggling the many tasks inherent to being a person apart from care arrangement, tasks that do not politely cease to exist because the long-term care system is a fiery dumpster of despair.

Medical appointments.

Follow ups on wheelchair parts that seem to be floating in the abyss.

Family obligations.

Medication refills.

Organizing your disastrous mountain of catheters and syringes.

Maintaining your friendships.

Ironically, most of these auxiliary tasks cannot be accomplished without a reliable care team.

Are you stressed out yet?

Burnt out, even?

Maybe you’d like to cry about it in the shower.

Well, I have awkward news to share. You can’t, unless someone puts you in the shower, and even then, you won’t be alone, and will likely feel pressured to hold it together, as not to make your assistant uncomfortable at the sight of your raw emotion.

That’s another strange feature of this existence as a care recipient… even in my most fragile moments… the unexpected death of a college friend, the slow, heart- wrenching decline of my beloved grandmother and later, her death, the occasional afternoon when I have simply had enough of the unrelenting nerve pain dripping its acidic terror across the back of my legs…

Even then, I will have a witness.

Do you know what that’s like?

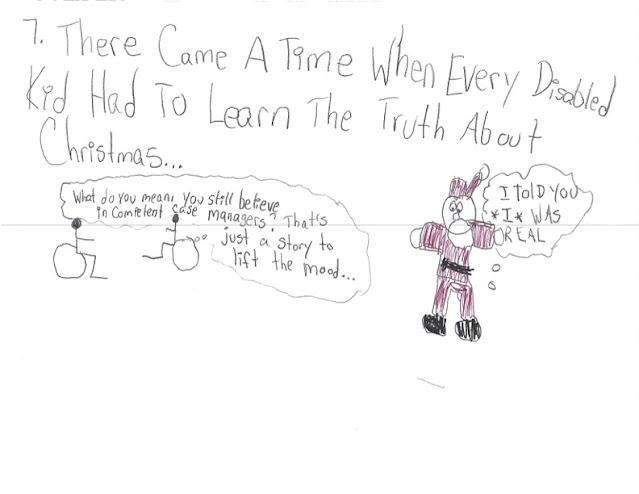

Despite the undeniable anxiety, grit, and Squidward meme- level nocturnal rumination involved in arranging care and trusting your body to a stranger, a quick Google search for “care recipient burnout” yields few results… and typically redirects to thousands of thinkpieces, blog posts, and Instagram reels on the exhaustion felt by the caregiver alone.

It is almost as though we are invisible to the media, to the government, and to average citizens, most of whom are content to let our patchwork care system crumble until it affects them personally.

With the paltry selection of existing media coverage about care recipients mainly focused on elders, the young face an even more isolating and draining experience, especially those who have never for even a moment known a life without needing care.

For us, arranging caregivers is not a “maybe” task in the distant future, reserved for the last two years of a lifetime.

It is a lifelong certainty with no days off, a commitment we cannot abandon without abandoning ourselves.

I want to be clear that I have a good life in spite of and because of my disabilities.

I believe that being a care recipient has given me a better understanding of what it means to be alive.

I am more equipped to meet others in their suffering and in their realizations of our glorious human fragility.

I am grateful to understand at a younger age than most do that nobody, not even people with blue-ribbon can-do attitudes, moves through this world alone.

And still, being a care recipient from the moment I burst into being is so, so, so hard.

There are few spaces devoted to exploring this particular stress and organizations in the care space seldom ponder the burden shouldered by care recipients.

Mental health counselors and psychologists remain ill-equipped to wrestle with this specific stressor that is all at once unique and astoundingly common.

News articles, documentaries, and photo essays rarely explore the opportunities stolen from us by a care system based in poverty… rarely consider the ways the receipt of care has fundamentally altered our identities, our relationships, and our concepts of privacy, autonomy, and intimacy.

There is hardly a mention anywhere of educations cut short, jobs lost, and social lives made minimal by the chronic shortage of reliable care.

Even some people within the disability sphere are quick to attribute these snuffed chances and fizzled dreams to a lackluster effort in the pursuit of #IndependentLiving, a concept which I should note can only look the way they think is worthy of praise.

Most of our non-disabled peers do not engage with the topic of care at all, as if they are afraid that if they look too long in our direction, they may become us.

They have told us, often overtly, that needing assistance with showering, using the bathroom, and eating, to them, represents an unacceptable loss of dignity.

Their discomfort and tacit disgust at the thought of needing care serves to ensure that our stories and our struggles remain unseen and unheard.

I am resolute in my assertion that we must continue to discuss both caregiver burnout and our best efforts to combat it.

But as the care crisis rages on, we can’t forget another equally valid perspective at the center of the storm: that of the care recipient.

Let us turn our well-deserved frustrations away from each other and toward the powerful bureaucrats who will gladly sacrifice our well-being to save a dime.

We are fighting the same grueling, perpetual battle while politicians casually divest from our survival.

Care recipients like me are rarely asked for their opinions on the subject, but let me make mine clear: Caregiver burnout is real, and this problem demands compassionate solutions.

But caregivers are not the only ones fighting their way through the flames.

Care recipients also live in the midst of a five-alarm fire, and we too are burnt to a crisp.